Rebecca Kimmel sat in a small room, stunned and speechless, staring at the baby photo she had just unearthed from her adoption file.

It was a black-and-white shot of an infant, possibly taken at an orphanage in Gwangju, the South Korean city where Kimmel had heard all her life that she’d been abandoned. But something about the photo — the eyes, the ears, an uneasy feeling deep in her gut — confirmed what she’d long suspected: This baby was not her.

Overcome, she started howling like a strange, wounded animal. This photo meant that the stories she had been told about herself were a lie. So who was she? Who IS she?

Thousands of South Korean adoptees are looking to satisfy a raw, compelling urge that much of the world takes for granted: the search for identity. Like many of them, Kimmel has stumbled into a web of switched photos, made-up stories and false documents, all designed to erase the very identity she desperately wants to find.

These adoptees live with the consequences of a tacit partnership by the South Korean government, Western nations and adoption agencies that has supplied some 200,000 children to parents overseas, despite warnings of widespread fraud.

For decades, South Korea tried to get rid of children from biracial parents, poor families, orphanages and unwed mothers, ignoring illicit practices. Western families in turn were eager to adopt from abroad, after access to birth control and abortion crushed the supply of domestic babies. While many adoptions ended happily, the desires of both sides also resulted in the unnecessary removal of generations of children from their families based on fake paperwork.

As Kimmel sat weeping in that room in the Seoul adoption agency, she knew little of this background. All she knew was that she needed answers.

She would find them — just not the ones she wanted.

Kimmel, an artist, thinks she is about 49; her exact age is one of the many things about herself she does not know. She throws herself with intensity into almost everything she does, particularly her all-consuming quest for her roots.

It wasn’t always that way. Kimmel spent much of her childhood in what many adoptees call “the fog” — a time of happy ignorance when they are oblivious to questions about their adoption.

Her parents told her the origin story they’d gotten from the adoption agency: She had been abandoned as an infant on a street in Gwangju and sent to an orphanage by police. A slip of paper on her clothing listed her birth date as the day before: Aug. 4, 1975.

There was no information about her biological mother or father. Her birth name was either Chung Jo Hee or Chung So Hee — the writing on the original paperwork was unclear.

She was adopted six months later by a family on the U.S. East Coast. Each Jan. 21, her parents would celebrate “Arrival Day,” a sort of second birthday that she saw as slightly embarrassing but sweet. They would display her documents and baby pictures.

But a small detail nagged at her: One photo that her parents showed from South Korea didn’t look much like those of her in the United States. When she asked why, her parents just told her that babies change.

“I think my parents were just happy to have got a child,” she says.

In 1986, the family traveled to South Korea, where adoption workers told them to visit a different orphanage than the one they’d thought Kimmel was from. It was called Namkwang, in Busan. They found no record of Kimmel.

Kimmel didn’t think much of it. Back in Maryland, she was living a suburban American childhood of Michael Jackson and Madonna and malls. She went to college, moved to Los Angeles, taught and ran an art school.

But a sense of loneliness crept in and became increasingly harder to ignore. Every now and then, the thought occurred to her: Was she just a girl from Maryland? Was that all?

“It didn’t seem very exciting,” she says. “It just seemed kind of like a blank slate.”

Kimmel marks 2017 as the year when the fog began to clear. One day, while searching the web for Korean makeup tutorials, she Googled “Korean adoptions,” and fell into a whole new world.

In 2017, she went to a three-day event in San Francisco with hundreds of Korean adoptees. The new ideas and friendships prompted a deep sense of urgency.

She realized she was running out of time. If she was 42, how old would a birth parent be?

How late was too late to find your roots?

The Korean adoptee diaspora is thought to be the largest in the world, with thousands returning to South Korea in recent years to look for their birth families. Fewer than a fifth of those who asked the South Korean government for help with their search were successful, records show. A big problem is that documents were often left vague or outright falsified to make children look “abandoned” even when they had known parents.

In 2018, Kimmel shut down her art classes and made a trip to South Korea that so many had done before her. She was brimming with excitement.

The clinic where Kimmel was supposedly dropped off was closed, but a former doctor who had worked there recalled an orphan who had been found in front of it.

“Oh God, this is me,” Kimmel thought, tears welling in her eyes.

But it was the first of many false starts. Unlike Kimmel, that orphan had been looked after by a grandmother for a while.

Kimmel next visited Korea Social Service in Seoul, her adoption agency. There, she argued heatedly with a social worker who had started working at KSS in 1976, the year of her adoption.

Could she get a copy of her file? No.

Could she photograph her file? No.

Could the social worker photograph or photocopy her file for Kimmel? No.

Kimmel realized the agency did not see her identity as hers.

“Never in my life have I been more angry,” she says. “There’s always this typical argument between adoptee and a social worker in Korea where the adoptee says, ‘That’s my information.’ And the social worker says, ‘That’s our information. It doesn’t belong to you.’”

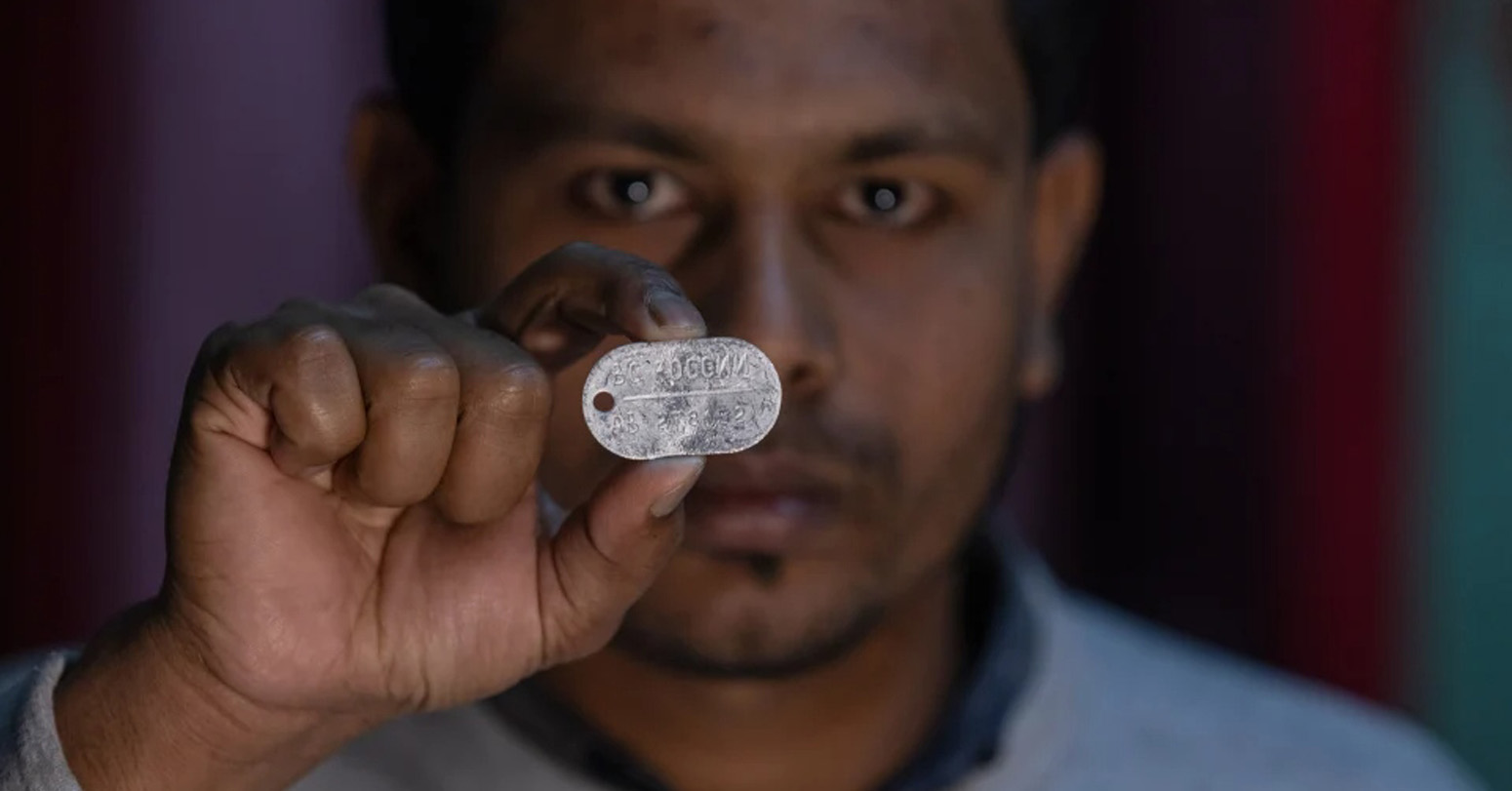

Kimmel fought until she was allowed to see her file. In the very back, she discovered a small square paper envelope with a photograph.

It was similar to the one she had questioned with her parents, but shot from a different angle. And this photo made it clear: The girl was not her.

“I’d opened this Pandora’s box,” she says. “And I didn’t feel like I could close it.”

She joined multiple online forums where adoptees shared stories about their lives, their birth searches, their grievances. She posted photos of the girl in her adoption file and of herself when she first arrived in the United States, asking if they looked like the same person.

Some said no. Others, including parents of adoptees, reacted as Kimmel’s parents had, saying “babies change.” A new hunch began to emerge: Had KSS switched her identity with another girl?

It had happened before. During a stay in Europe, Kimmel had been startled to meet several adoptees in Denmark who at the last minute were given the paperwork of other children.

Kimmel had her adoption photos cross-checked by a dysmorphologist, a medical expert trained to identify birth defects in children, mainly from facial features. He saw distinctive differences in the ears and the area between the nose and upper lip. His conclusion: These were likely different girls.

“At that point I realized, oh my God, I went through all of this trial and trepidation to photograph a file that’s not really mine,” Kimmel says. “It has my adoptive parents’ names; it’s a file that’s related to me. But the actual physical child is not me; the identity is not mine.”

So who was Kimmel? And who was the other girl?

-AP

Middle-aged man spends millions to

Dr. Dharam Raj Upadhyay: Man

Children, Greatest Victims Of Sudan’s

Breathing The Unbreathable Air

Comprehensive Data Protection Law Critically

Gender Differences In Mental Healthcare