By Kelly Grovier, 14 of the most startling photos from this year – including Ukrainian soldiers playing chess with Molotov cocktails, Iranian protesters and wildfires in Spain and the US – and compares them with iconic artworks.

- Credit: Diego Reyes/AFP/Getty Images

- Credit: Diego Reyes/AFP/Getty Images

A man sits on a lawn chair holding a pretty pastel parasol against the blazing sun, seemingly oblivious of the apocalyptic plumes of smoke billowing up from the burning tyres, a few feet away, that are scattered across the highway on which he is surreally perched. Impeding access to Iquique, a city in northern Chile near the border with Bolivia, where groups agitating against illegal immigration have organised protests, he is an implausible paragon of imperturbable calm.

The incongruity of his relaxed posture (which rhymes with the idyllic beach, sparkling sea, and poetic palm tree pattern repeated on his parasol) and the chaos raging around him is reminiscent of several Surrealist paintings from the 20th Century – such as Salvador Dalí's Sewing machine with Umbrella (1941) – that portray the ostensibly innocuous object as absurdly foretokening doom.

- Credit: Yasin Akgul/AFP via Getty Images

- Credit: Yasin Akgul/AFP via Getty Images

When Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman, died in a Tehran hospital under suspicious circumstances on 16 September, women around the world began cutting their hair in protest against her treatment by the government of Iran. Amini had been arrested three days earlier by the Islamic Republic's Guidance Patrol – a vice squad enforcing the Islamic dress code – for allegedly wearing the hijab incorrectly. While in the custody of the morality police, according to eyewitnesses, Amini suffered terrible physical abuse and fell into a coma.

Photos of Nasibe Samsaei, an Iranian woman living in Turkey, cutting off her own ponytail as a display of solidarity and defiance outside the Iranian consulate in Istanbul, went viral. As a statement of intent to control one's own physical presence in this world, the act of cutting one's own hair short has proved perennially powerful. In her 1940 painting Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair, created a month after her divorce from the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo allows us to observe her almost mid-snip, with scissors still in her hand, as strands of the self, she once felt she had to be lying scattered all around her.

In July 2022, Nasa released a breathtaking photo of a young star-forming region of the nearby Carina Nebula. Captured by the agency's new James Webb Space Telescope, the image, which resembles the undulations of mountains and valleys, allows us to see for the first time previously invisible areas of star birth. Our instinct to read the distant stellar spectacle in the terrestrial language of landscapes is hardly new and can be glimpsed in the terrene contours of a 15th-Century Aztec map of the cosmos.

The elaborate deerskin diagram places the fire god Xiuhtecuhlti at the celestial map's centre, surrounded by cosmic trees flaring out in all four directions as if the heavens were an undiscovered forest of sublime symmetry waiting for us to wander and explore.

While increasingly familiar, the sight of flames consuming homes during the summer wildfire season in California never ceases to horrify. For nearly three weeks from the end of July, the so-called Oak Fire in the state's Mariposa county destroyed almost 200 buildings. An image captured of the flames ravaging the interior of a home was ferociously affecting. Silhouettes of a family's dining room table and chairs flicker devilishly against a tsunami of heat that, moments later, vapourised the space into memory. There is no aesthetic parallel possible for such appalling destruction.

A painting by the British artist JMW Turner of a drawing room in a great house engulfed by sunlight, which the artist encrusted with the fiery pigment using his fingernails, palette knife, and brush end, may have once seemed menacing in its imaginary ignition. By comparison with Noah Berger's photo from Maricopa county, the canvas feels playfully poetic.

- Credit: Chris McGrath/Getty Images

- Credit: Chris McGrath/Getty Images

Two weeks after Russian forces illegally invaded Ukraine, photos of a game of chess played by members of the Territorial Defence unit, charged with guarding a barricade on the outskirts of eastern Kyiv after curfew, went viral. What was so compelling about the midnight match, apart from the outsized board on which the game was being played on a patch of dirt in the freezing cold?

The pieces had been fashioned not from wood, ivory, resin, or plastic as is typical, but lethal Molotov cocktails – pointedly typifying the huge and incendiary stakes of the new war. The image of soldiers seated at a chess board that symbolises the larger conflict deepening around them calls to mind the intense geometries of French artist Jean Metzinger's cubistic painting Soldier at a Game of Chess (c 1914), created in the early months of World War One. Intimate knowledge of the horrors of war, which Metzinger witnessed at close range as a medical orderly stationed in north-east France, ignites with poignancy his highly charged canvas.

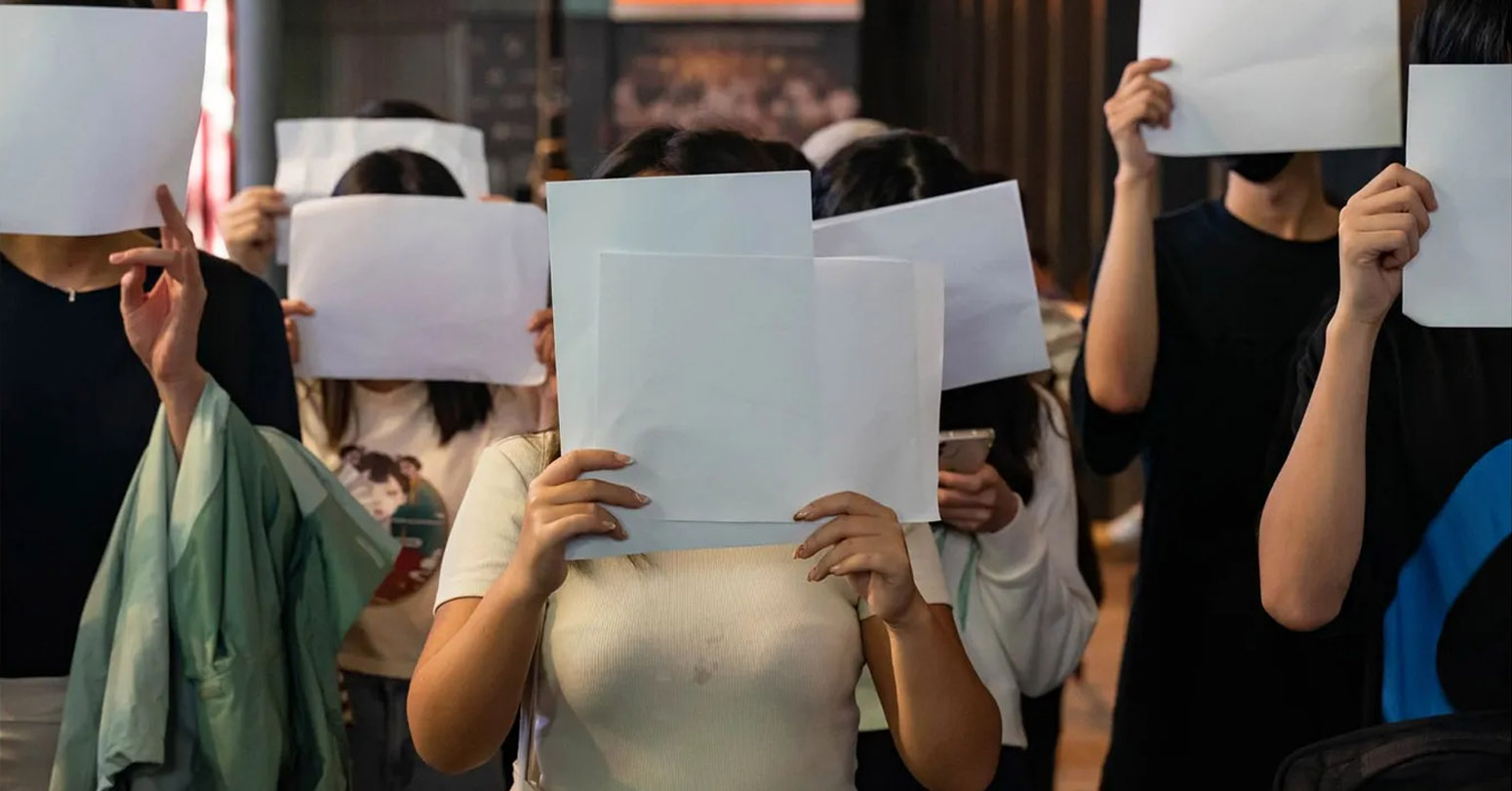

- Credit: Anthony Kwan/Getty Images

- Credit: Anthony Kwan/Getty Images

In November 2022, protestors holding blank sheets of paper in front of their faces took to the streets and squares of many Chinese cities to protest against the country's unyielding Covid restrictions. The gatherings were prompted by an apartment fire in Xinjiang province that resulted in deaths that many insisted could have been avoided had such strict policies not been in place. The blank sheets of paper held up by the demonstrators came to symbolise everything that the protestors were not allowed to express publicly – a blinding mask of silence and anonymity.

The eloquence of emptiness in Chinese visual culture has a long history and can be traced back to the powerful use of negative space in traditional scrolls. In the 13th-Century Song Dynasty depiction of A Returning Sailboat from a Distant Shore (from The Eight Views of the Xiao Xiang Region), an economy of ink strokes might articulate the poetic scene but it is the mastery of blankness in which they swim – the ocean of annihilating white – that marvels the eye.

- Credit: Skanda Gautam/Zuma/Rex/Shutterstock

- Credit: Skanda Gautam/Zuma/Rex/Shutterstock

A photo of three young novice monks, clad in traditional crimson robes, sweeping a pavement along a road outside the Buddhist monastery in Godavari, in the southeast of Kathmandu, seems to gleam outside of time. It isn't simply the static stoop of the figures, suspended forever in their back-breaking task, that echoes French Realist Jean-François Millet's painting of three women gleaning stalks from a field. The two scenes seem sculpted from the same exquisite softness of shadow and light.

(Credit: Reuters/Adrees Latif/ Alamy)

(Credit: Reuters/Adrees Latif/ Alamy)

Under cover of night and illuminated only by the glow of a torch, a raft of asylum-seeking migrants from Central America embark on a dangerous journey to the US in June 2022. While no work of art could ever capture or anticipate the intensity of anguish and emotion that unsettles the poignant scene, the tense nocturnal trek, sculpted from darkness by the impassive torch's bare blare, glimmering off the inky water of the Rio Grande River, in Ciudad Miguel Aleman, Mexico, calls to mind the affecting atmosphere of German Baroque artist Adam Elsheimer's influential portrayal of the Holy Family's fearful moonlit flight from Herod.

Elsheimer's oil-on-copper cabinet painting The Flight into Egypt has been hailed as the first naturalistic depiction of the night sky in Renaissance art and was likely the last work that Elsheimer created before he died in 1610, aged just 32.

In July 2022, two supporters of the environmental activist group Just Stop Oil, which demands that the UK government halt new fossil fuel licensing and production, glued themselves to the frame of Romantic artist John Constable's famous landscape The Hay Wain, after covering the surface of the work with a nightmarish parody of the scene.

Where the original painting portrays a picturesque scene of horses pulling a wagon across the River Stour in East Anglia, the protestors' dystopian vision depicts the area destroyed by unchecked encroachments on the environment, as low-flying aeroplanes, abandoned cars, and a sprawling tarmac destroy Constable's dream.

- Credit: Twitter account of Elon Musk/AFP via Getty Images

- Credit: Twitter account of Elon Musk/AFP via Getty Images

In October 2022, the billionaire businessman Elon Musk shared a video of himself lugging a kitchen sink into the headquarters of the social media platform Twitter, which he had just purchased. Musk attached to the video the punning caption, "let that sink in". It was not, of course, the first time that someone mischievously shoved a hunk of glazed ceramic in the world's face in order to alter the way it perceives cultural communication.

When the French avant-garde artist Marcel Duchamp, who famously adored chess, tipped a readymade urinal on its side, signed it with the nom de plume "R Mutt", and proposed it as a work of art in 1917, the audacious act was seen as the opening move in a long game that he was playing with the art world. In the end, Duchamp won, by convincing the public that the nature of art is never fixed. How, exactly, Musk's high-stakes match with investors and users of social media ends is anybody's guess.

- Credit: Nathan Howard/Getty Images

- Credit: Nathan Howard/Getty Images

The decision taken by the US Supreme Court in the summer of 2022 to overturn an earlier ruling it had reached in 1972 when it guaranteed a woman's right to an abortion, was met with passionate protests by pro-choice supporters. The photo of one such activist, Sam Scarcello, who soaked herself in fake blood outside the court on Independence Day, was especially arresting.

The implication that the nation's highest court had, by its decision to allow individual states to limit access to abortion, left her bleeding and all but sacrificed on the icy altar of its snow-white steps echoed the dynamics of early work by the celebrated Serbian conceptual artist Marina Abramovic. In 1975, for her performance piece The Lips of Thomas, Abramovic carved stars into her stomach with a knife while stretched out naked on a block of ice, as if daring anyone from the audience to intervene and stop the pain. No one did.

- Credit: Ian Berry/Magnum Photos

- Credit: Ian Berry/Magnum Photos

Few photographs that documented the outpouring of grief that followed the death of Queen Elizabeth on 8 September were as memorable as this eerie image of Prince George, watching the State Hearse carrying his great-grandmother. Captured from a television broadcast of the Hearse's progress towards Windsor, the photograph manages to merge a poignant portrait of the Prince, who is second in line to the throne, and the mournful crowds that lined the road, suspending the past, present, and future in a single affecting frame.

That ability to fuse lucent layers of materiality and emotion recalls a remarkable series of urban-reflection paintings by the Northern Irish artist Colin Davidson, for whom Queen Elizabeth sat in 2016. Though Davidson is best known for his large-scale, impassioned impasto portraits of everyone from Brad Pitt (whom he taught to paint) to Angela Merkel, his canvases chronicling the luminous life of cafe windows, in which intimate interior spaces merge miraculously with hustle of the congested street outside, is nothing short of hypnotic.

- Credit: Sxenick/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

- Credit: Sxenick/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

A photo of Spanish firefighters battling a blaze in the village of A Cañiza, Pontevedra, seems to have roared to life from the pages of a medieval manuscript. Suggesting itself as a menacing mascot for what has reportedly been the worst year for wildfires in Spain in three decades, this slithery eruption of the Galician fire briefly assumed the sinister shape of a sinuous dragon, as if mimicking the smouldering, sinewy snarl of a historiated "S" from a 12th-Century Netherlandish choir book.

- Credit: David Ramos - Fifa/Fifa via Getty Images

- Credit: David Ramos - Fifa/Fifa via Getty Images

A joyful photo of the Argentine forward Lionel Messi, carried on the shoulders of his teammates as he celebrates his country’s victory in the final match of the World Cup against France, proved infectious no matter which team one was supporting. The image of such unbounded jubilation stood out in a year that has witnessed so much upset and suffering. Precise parallels for such exultation in art history, which is itself more prone to portraits of sombre reflection, isn't straightforward. But there is something about the euphoria expressed by the 17th-Century Dutch artist Gerard van Honthorst's painting The Laughing Violinist, that likewise insists on a smile.

-BBC

- Credit: Nasa

- Credit: Nasa - Credit: Noah Berger/AP

- Credit: Noah Berger/AP - Credit: Kirsty O'Connor/PA

- Credit: Kirsty O'Connor/PA

Comprehensive Data Protection Law Critically

Gender Differences In Mental Healthcare

Messi Wins Best FIFA Men’s

Erosion of Democracy

Fly Dubai Catches Fire in

“Complexities of the South Asian